Mecklenburg Declaration of Independence

250 Years Ago

On April 30, 1819, the front page of the Raleigh Register and North-Carolina Gazette featured a manuscript titled “Declaration of Independence.”

The text of the article was not that of the well-known United States Declaration of Independence of July 4, 1776. Instead, it appeared to be a declaration made by the citizens of Mecklenburg County, NC, “more than a year before Congress made theirs.”

The Mecklenburg Declaration of Independence was said to have been signed 250 years ago on May 20, 1775, by a group of 26 to 28 men who were–with perhaps one or two exceptions—all Presbyterian.

Mecklenburg’s Presbyterian churches were more than places of worship; they were community hubs where people socialized, educated their children, and engaged in political discourse.

Presbyterianism, which emphasizes self-governance, personal responsibility, and moral clarity, played an important role in influencing revolutionary thought at the time.

In the declaration, the residents of Mecklenburg County wrote that they were: “a free and independent people…under the control of no power other than that of our God and the General Government of Congress.”

If this was the first declaration of independence in the colonies, the Mecklenburg Declaration was revolutionary–-and also extremely risky.

The men who signed their names to it–-committing the capital crime of treason against the crown of England–-had essentially signed their own death warrants.

So why was this extraordinary act seemingly forgotten until it was published in 1819, nearly 45 years after it was written?

Rediscovery of the Declaration

The text printed in the Raleigh Register was not the original Mecklenburg Declaration, which was said to have burned in a house fire in April 1800. What appeared in 1819 was reportedly a reconstruction made a few months after the fire by John McKnitt Alexander, the clerk who recorded the original in 1775. This reconstruction resurfaced as interest in the revolution reignited in the years after the War of 1812.

In 1818, during a US Congressional debate over whether the Revolution began in Virginia or Massachusetts, NC’s representatives insisted that the people of Mecklenburg had been the first to declare independence. To prove NC’s important role, John McKnitt Alexander’s son, Dr. Joseph McKnitt Alexander, was asked to look through his father’s papers and write an article about the Mecklenburg Declaration.

Dr. Alexander used a document he found in his father’s “old mansion house in the centre of a roll of old pamphlets,” to write an account of what had occurred. He sent the account to the representatives, who brought it to the Raleigh Register for publication. This publication ignited a fierce debate over the authenticity of the Mecklenburg Declaration, a debate that still endures today.

Thomas Jefferson’s Response

When former US President Thomas Jefferson, the primary author of the US Declaration of Independence, received a copy of the Mecklenburg Declaration of Independence from his former Vice President, John Adams, in June 1819, Jefferson quickly dismissed it as “spurious.” He wrote, “Would not every advocate of independence have rung the glories of Mecklenburg County in N. Carolina…? Yet the example of independent Mecklenburg County, in N. Carolina, was never once quoted…. I shall believe it [as a fabrication] until positive and solemn proof of its authenticity be produced.”

John Adams, on the other hand, considered it plausible that Jefferson had “copied the spirit, the sense, and the expressions of [the Mecklenburg Declaration] verbatim, into his Declaration of the 4th of July, 1776.”

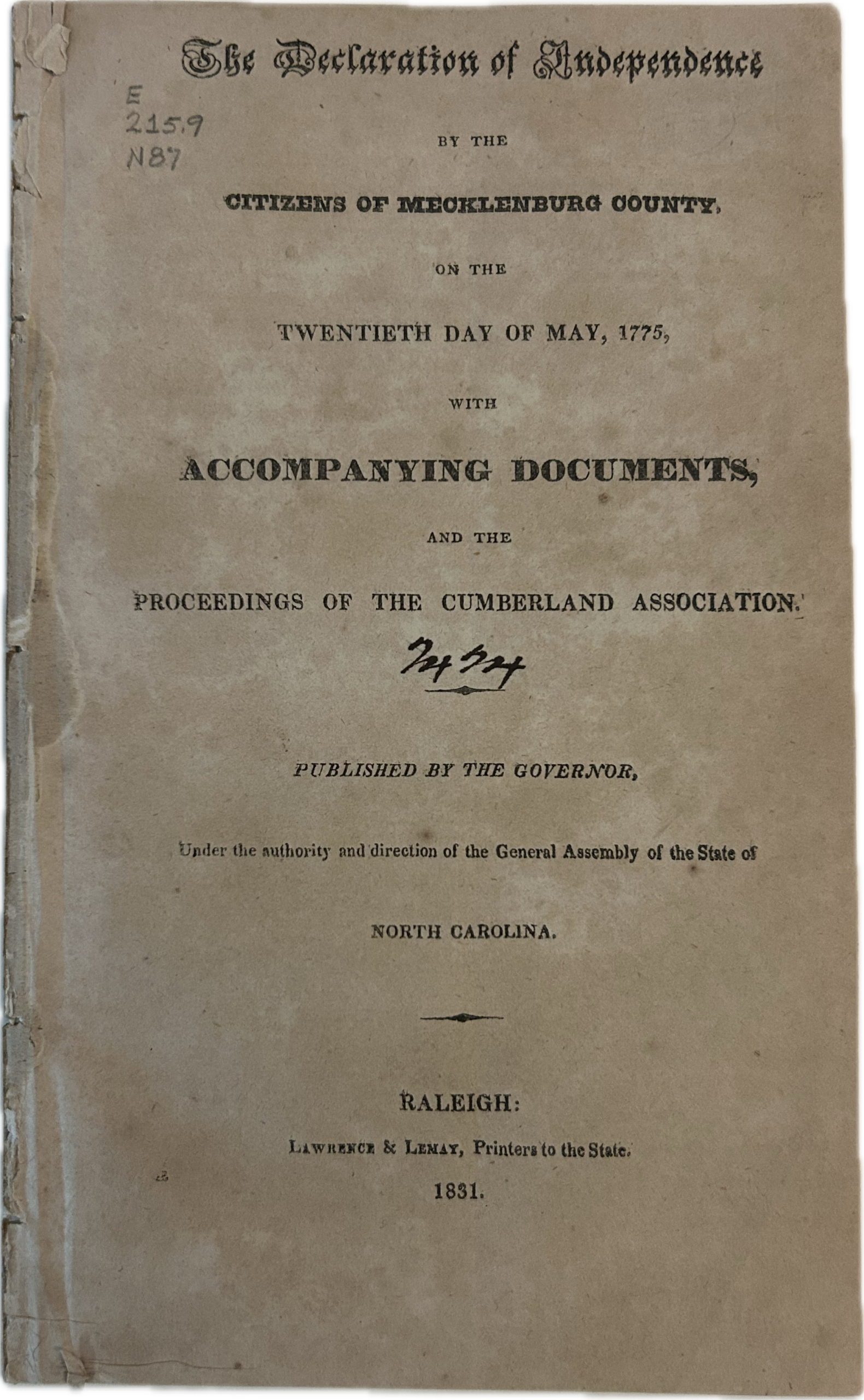

Though Jefferson’s dismissal of the Mecklenburg Declaration was published in various newspapers shortly after he learned of it, his concern did not become widely known until 1829, with the release of The Works of Thomas Jefferson. This revelation prompted NC’s Governor to task a committee with investigating Jefferson’s claim. In their 1831 report, the committee concluded that “Mr. Jefferson was mistaken.”

Discovery of the Mecklenburg Resolves

In 1838, a discovery reignited the debate over the authenticity of the Mecklenburg Declaration. Peter Force, a historian and archivist, uncovered a printed copy of a document called the Mecklenburg Resolves in the June 3, 1775, edition of the Massachusetts Spy.

The Resolves, a series of 20 resolutions adopted by Mecklenburg leaders on May 31, 1775, severed ties with Britain and established local governance.

While this confirmed revolutionary activity in Mecklenburg in May 1775, the Resolves’ tone was far more cautious than the bold language of the Declaration, which had purportedly declared independence just 11 days earlier, on May 20, 1775.

This raised the questions: if the Resolves had been published shortly after they were written, why could no contemporaneous copy of the Declaration be found? And, why would Mecklenburg’s leaders have written two similar documents within weeks of each other?

Supporters of the Declaration insisted that the two documents served different purposes. They argued that the Declaration, issued on May 20, was a bold proclamation of independence meant to rally local support, while the Resolves, drafted on May 31, were a more measured and structured response intended for public distribution. According to this view, the Resolves did not replace or contradict the Declaration but instead provided a practical framework for self-governance in the absence of British authority.

Many also pointed to the character of the Declaration’s signers—respected elders and Presbyterian leaders from churches like Sugaw/Sugar Creek, Hopewell, and Poplar Tent—arguing that men of such conviction and integrity would not have falsely claimed to issue a declaration of independence.

Critics, however, saw the Resolves as evidence that the Declaration was a later invention. If Mecklenburg leaders had already outlined a careful rejection of British rule in the Resolves, why would they have issued an earlier, far more radical declaration that was never recorded in contemporary newspapers?

Some suggested that John McKnitt Alexander, who had lost the original document in a fire, may have reconstructed the Declaration decades later from memories of the Resolves, unintentionally blending fact with patriotic embellishment. Others believed that by the time the Declaration surfaced in 1819, a strong desire to highlight North Carolina’s revolutionary role had led to the creation of a dramatic but unsubstantiated narrative.

As we commemorate the 250th anniversary of independence, perhaps the question isn’t whether the Declaration is authentic—it’s how its legacy continues to shape our understanding of freedom, independence, and equality.

As we reflect on this legacy today, we are reminded that the fight for liberty and equality is ongoing, and that the ideals of independence must be continually examined, redefined, and fought for.